WOMEN CONTROL FERTILITY

CONTRACEPTION AS FREEDOM

A woman’s ability to control her own fertility stands as one of the greatest discoveries of all time with the benefits accruing to all of humanity, but especially to women and girls. Contraceptive use has the potential to directly transform the lives of half of the world’s adult population, indirectly improve the lives of the other half, and dramatically improve the quality of life of the generations of children born in societies where contraception is widely used.

Contraception, perhaps more than any other single intervention, gives women the freedom to control their own futures and to reduce and even eliminate one of the greatest threats to the quality of their lives and to the fulfillment of their potentials – unplanned pregnancies. There are an estimated 121 million unplanned pregnancies every year, and 134 million births, according to the United Nations.

Contraception is a lifesaving medical intervention that already prevents the deaths of hundreds of thousands of women in pregnancy and childbirth and millions of newborns. If all demand for modern contraception was met for the women who want to use it, and they were also provided with quality pregnancy and childbirth care, maternal and newborn deaths would fall by a massive 62% and 69% respectively, according to the Guttmacher Institute. No other single intervention has the power to reduce maternal and newborn deaths to these levels.

Further, the positive impact of contraception on women’s ability to learn and earn is significant. Studies in the USA by Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz and Martha Bailey and Jason Lindo have found that women’s access to the contraceptive pill in the 1960s and 1970s accelerated delays in marriage and childbirth and increased women’s labor force participation, especially in non-traditional, professional jobs.

There is now an emerging body of evidence that increasing access to contraception is having the same impact in low- and middle-income countries, summarized in the 2012 Lancet Series on Family Planning. When these individual benefits are aggregated at the national and global levels, the returns to investments in contraception are very high. A 2014 analysis by Hans-Peter Kohler and Jere Behrman concluded that estimates of the benefit-cost ratios for contraception are in the order of 120:1, meaning benefits exceed costs by a multiple of 120.

One of the reasons that investments in contraception can deliver such potentially massive returns is the role they can play in triggering the “demographic dividend,” which delivers a rise in incomes, if conditions are right, from a higher share of working-age people in the population (and fewer dependent children). For example, meeting all unmet needs for modern contraception could increase GDP per capita in Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal by between 31% and 65% according to an analysis by David Bloom and colleagues.

UP TO ONE BILLION WOMEN EXPOSED TO UNPLANNED PREGNANCY

Despite the strong evidence that increasing contraceptive use accelerates development, more than one half (52%) of the world’s 2 billion women aged between 15 and 49 are not using modern contraception. For the subset of women who are seeking to get pregnant, who are pregnant, or who have recently delivered, this is not a problem. But for the rest, lack of contraceptive protection means exposure to the risks of sex without contraception – unplanned pregnancy.

Estimates vary as to the size of the pool of women who want to use modern contraception but who currently don’t. Most of these estimates underestimate the need by focusing only on married and partnered women or women in low- and middle-income countries (e.g., the Guttmacher Institute‘s estimate of 218 million women in need of modern contraception), or they rely on self-reported survey data that only counts women who have been sexually active in the past four weeks (e.g., a recent Global Burden of Disease modeling exercise estimated 163 million in need of modern contraception).

As a result, global contraceptive access initiatives like Family Planning 2030, studies like the 2012 Lancet Family Planning Series, and databases like World Contraceptive Use have struggled to come to terms with the size of the pool of women and girls who want to use modern contraception. Too little is known about the contraceptive status and preferences of single women and girls. It is highly likely that these women face an even higher demand for contraception and greater barriers to accessing it – and even to self-reporting their need – due to the stigma of sex and pregnancy before marriage in many countries. This places single women at a higher risk of unplanned pregnancy compared to their married and partnered peers.

Single women and girls may also be at greater risk of unwanted pregnancy from forced or coerced sex. Rates of sexual violence are high across all regions, but especially in Africa and South Asia where more than one in three women will experience partner violence in their lifetimes, according to new estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO). And in these regions, one-third of girls will experience an incident of sexual violence before they reach 18 years of age, according to the Violence Against Children surveys supported by the Together for Girls initiative. We should not underestimate the pregnancy risks to girls and single women in societies with low contraceptive use and high rates of sexual violence.

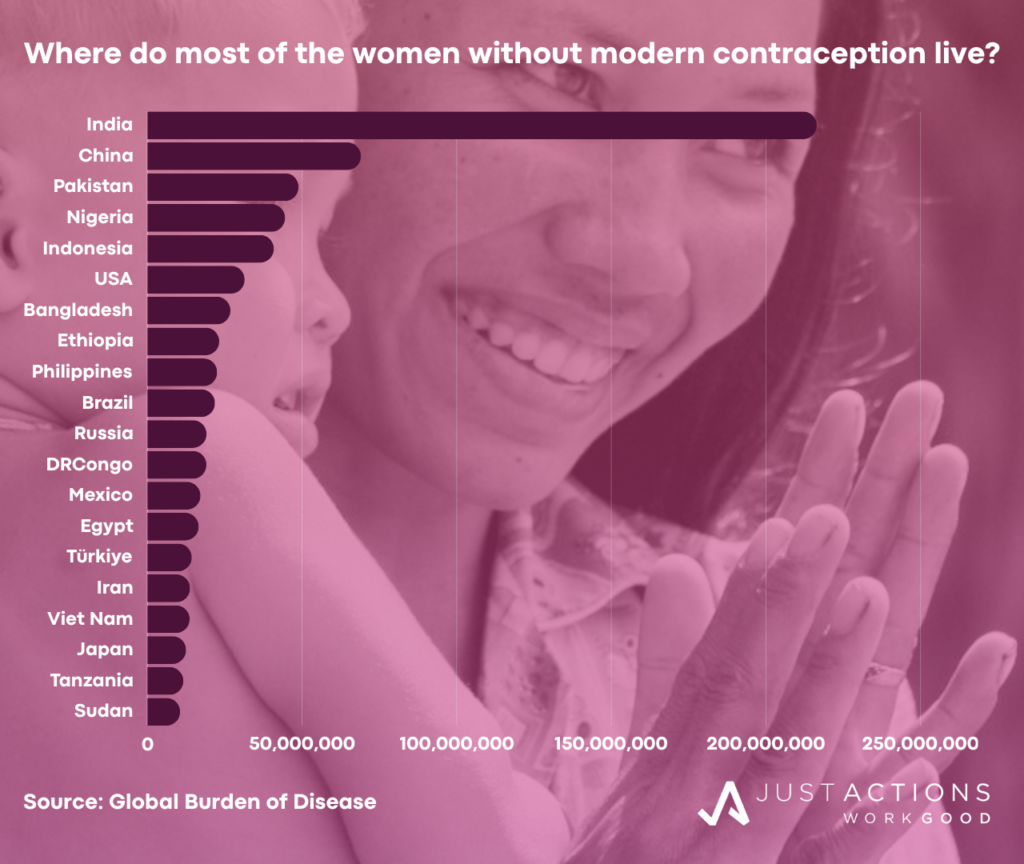

It is of great concern then, that the largest populations of unprotected women and girls are in Asia and Africa. India is home to 216 million women and girls who are not using modern contraception, China to 69 million, Pakistan to 50 million, Indonesia to 41 million, Bangladesh to 27 million, the Philippines to 23 million, and Viet Nam 14 million. The largest populations of unprotected women across Africa are in Nigeria (50 million), Ethiopia (23 million), Democratic Republic of Congo (19 million), Tanzania (12 million), and Sudan (11 million). Other countries in the top 20 include the USA, home to 31 million women and girls not using

modern contraception, Brazil (22 million), Russia (19 million), Mexico (17 million), Egypt (17 million), and Türkiye (14 million), Iran (14 million), and Japan (13 million). Together, these 20 countries account for 700 million (68%) of the estimated 1 billion unprotected women and girls.

Of special concern are the large populations of unprotected women and girls in the countries with extremely low modern contraceptive use (<20%) and high fertility rates (more than five children per woman). In addition to the Democratic Republic of Congo mentioned above, Niger, Central African Republic, Somalia, Chad, and Mali all record ratios above 2. In these countries, increasing modern contraceptive use could yield major national and regional development returns, including increased economic growth, reductions in poverty and inequality, and improvements in maternal and child health and education.

Further, due to the “youth bulge” in many of these countries increasing modern contraceptive use could also deliver a long-term “peace and security dividend.” By 2030 the number of young men (15 to 29 years) will have increased by more than 50% in most of the central and west African countries. The rising numbers of young men, many of whom will come of age during a period of high unemployment and rapid urbanization, could become a potent force for conflict and insecurity.

THE CHILD DEPENDENCY RATIO: A NEW DEVELOPMENT CONCEPT

In recognition of the economic and social costs of high fertility to individual women, their families and nations, and of the tendency for current measures of modern contraceptive use to underestimate the need, countries should adopt a measure called the Child Dependency Ratio. This ratio expresses the number of dependent children (less than 15 years of age) relative to the number of women of working age (15 to 49 years). It is a measure of the relative burden of childbearing and rearing that falls disproportionately on women of working age in most countries. This burden acts as a barrier to women’s and girls’ education and labor force participation in almost all countries.

For example, countries with Child Dependency Ratios greater than one have on average more than one dependent child per woman of working age, a level which can restrict women’s and girls’ freedom to pursue education and earnings and to contribute to economic growth and development, especially in societies lacking policies and programs to support mothers to learn and earn. In contrast, countries with ratios less than one have fewer than one child per woman of working age, a level at which women have greater freedom to pursue improvements in their quality of life and contribute to national development.

In 2023, the global Child Dependency Ratio was 1.025. For every single woman aged 15 to 49 in the world, there was just over one child aged under 15 years, according to United Nations data. The ratio varied widely across regions, from a high of 1.6 in Africa to .72 in Europe.

Among the 20 countries with the largest populations of girls and women exposed to the risks of unplanned pregnancy, eight have Child Dependency Ratios above one. The Democratic Republic of Congo recorded the highest ratio (2.09), followed by Nigeria (1.84), Tanzania (1.78), Sudan (1.69), Ethiopia (1.57), Pakistan (1.44), Egypt (1.3), and the Philippines (1.17). The remaining 12 countries all scored rates below one, ranging from Indonesia (0.96) to the lowest rate – Japan’s 0.61.

Of great concern are the countries with large populations of exposed women, very low modern contraceptive prevalence, high fertility rates, and Child Dependency Ratios above two. For every woman aged 15 to 49 in Niger, there are 2.36 children under 15 years. The ratio in Mali is 2.1, in Somalia 2.05, in Chad 2.04, and in Angola 2. Women in these countries are spending so much time bearing and rearing children in such challenging circumstances that it is undermining the quality of their own lives, their children’s lives and national development.

Child dependency is correlated with human development. The countries with the highest Child Dependency Ratios score the lowest on the Human Development Index, all of them in Sub-Saharan Africa, while the countries with the lowest Child Dependency Ratios score the highest in measures of human development – all are in Europe, except for Australia and Hong Kong.

NEW APPROACHES NEEDED TO ACCELERATE FERTILITY RATE DECLINES

In recent decades, progress in increasing the use of modern contraception and reducing fertility rates has been disappointing. Between 2000 and 2019 modern contraceptive prevalence among married/partnered women rose from 54% to just 56%, according to the United Nations (UN). Rates still vary widely across regions from 70% across East Asia and the Pacific to just 29% across Sub-Saharan Africa. Of special concern are the 33 countries where modern contraceptive prevalence is 20% or below, 24 of them in Africa.

New approaches are needed to accelerate fertility rate declines and trigger the demographic dividend under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is especially important in those Sub-Saharan African countries where continued high fertility and low modern contraceptive use threatens not only national economic and social development, but also peace and security. The ultimate goal of the new Child Dependency Ratio is to accelerate the rate of progress in reducing the fertility rate to the levels required for the achievement of the SDGs relating to health and gender equality.

Accordingly, the UN, its agencies, and development partners should support a new focus on reducing the Child Dependency Ratio by ensuring that all governments and UN agencies understand that reducing the burden of childbearing and rearing on women of working age will contribute to gender equality as well as national economic and social development. The UN should set a new national child dependency target of less than one child (0 to 14 years) per woman (15 to 49 years) by 2025 and less than 0.8 by 2030 and publish an annual Child Dependency Ratio for every country. The UN should also examine sub-national trends among certain populations of women, especially those on the lowest incomes who face both higher risks and costs associated with unplanned pregnancies.

New technologies and non-traditional allies that can bypass government bottlenecks and get information, products and services directly to the women most at risk are urgently needed. The 337 million women in the world who may want to use modern contraception but who currently don’t, represent one of the largest, under-served markets in the world. Pharmaceutical companies are producing ever better contraceptive products – longer lasting and with fewer side-effects – while for-profit and not-for-profit startups like nurx, The Pill Club, Lemonaid Health, Women on Web and Muso Health are finding ways to deliver contraception and safe abortion right to a woman’s doorstep. The vast private sector is still a relatively untapped source in the fight for fertility control.

A final note. Throughout this analysis the term “contraception” rather than “family planning” has been used because not all women and girls who use contraception are planning families. Many are seeking instead to prevent pregnancy and still others are using contraception for other purposes (e.g., to minimize complications from menstrual and other painful conditions). In this context, contraception is a simple and highly effective medicine that women take to prevent pregnancy, but also for other reasons, no different to a vaccine given to children to prevent polio or an antibiotic to treat pneumonia.

Having already transformed the quality of life for hundreds of millions of the world’s women and girls and with the potential to transform the lives of many millions more, and responsible for preventing the deaths of hundreds of thousands of women and many millions of babies, contraception may well be the world’s most life-affirming medical discovery.

Updated January 2024