Solving the global nutrition crisis

Bravo to the EAT-Lancet Commission for catapulting the global nutrition crisis to center stage as one of a handful of our most critical global challenges. The Commission’s work crests a wave that has been building since the first Nutrition for Growth Summit in 2013. In the years since, there have been four Global Nutrition Reports, 194 governments have adopted the most ambitious set of nutrition-related national goals, and the UN General Assembly has proclaimed 2016 to 2025, the “Decade of Action on Nutrition.”

Over the same period, there have been a plethora of nutrition initiatives, including the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement and business network, the Power of Nutrition Fund and Food Reform for Sustainability and Health (FReSH), Standing Together for Nutrition, to name a few. USCIB, leading business alliance, and NGO GAIN joined forces to produce a set of “Principles of Engagement” to encourage the public and private sectors to work together to address one of the greatest barriers to progress – the reticence of governments, businesses, UN agencies and NGOs to work with, rather than against, each other on nutrition.

But what now? How to take all of this activity and turn it into real action that reduces nutrition-related deaths and disabilities?

First, we need to know what is causing the most nutrition-related deaths to understand where immediate action can have the greatest impact on human health. Second, we need to identify the largest populations at greatest risk of nutrition-related death, by age and gender to know which populations to target. And third, we need a list of the countries where nutrition-related deaths are concentrated in order to fully engage the right set of governments and non-state actors. This information will help prioritize the right issues, populations, and actors so that investments have the greatest possible impact on the global nutrition crisis and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

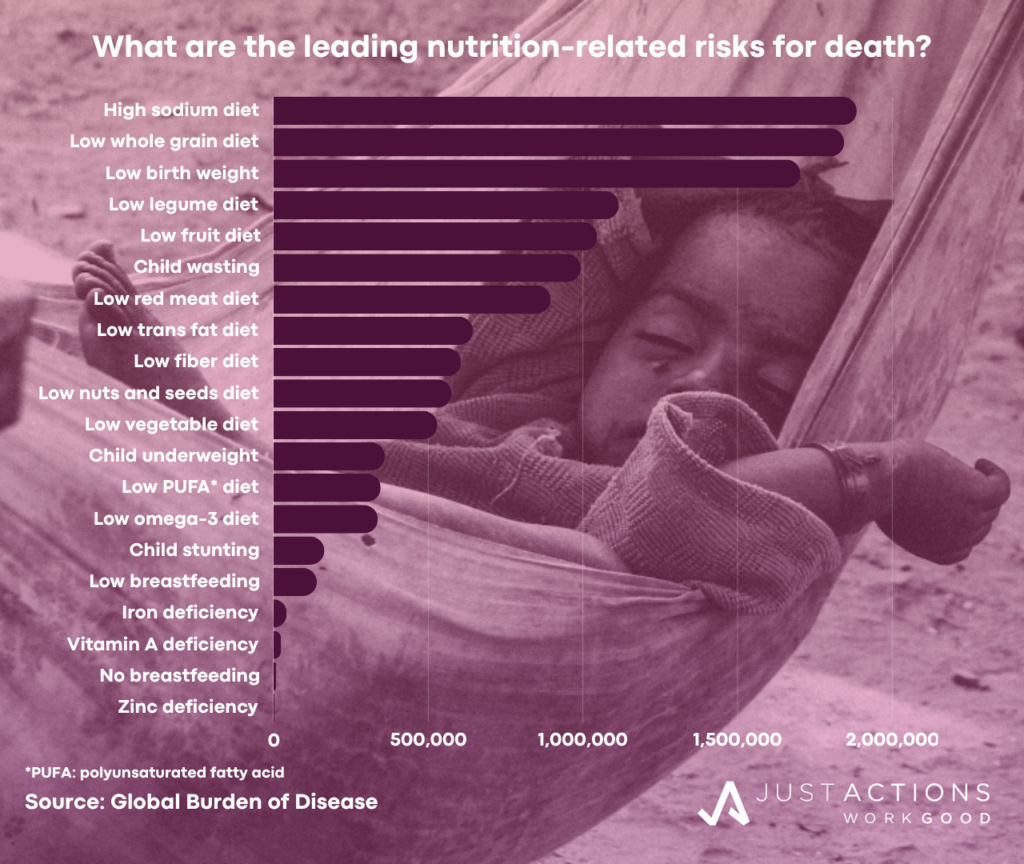

What causes the most nutrition-related deaths?

Malnutrition is not a leading direct cause of death, but is a major risk factor for death from other causes. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD), malnutrition killed an estimated 252,000 people directly in 2019, but was a risk factor in a massive 10.8 million deaths. The twenty risks responsible for the majority of nutrition-related deaths include high sodium diets, low whole grain diets, low birth weight, low legume diets, low fruit diets, child wasting, high red meat diets, high trans fat diets, low fiber diets, low nuts and seeds diets, low vegetables diets, child underweight, low poly unsaturated fatty acid diets, low omega-3 diets, child stunting, low breastfeeding, iron deficiency, Vitamin A deficiency, no breastfeeding, and zinc deficiency.

Diet-related deaths have risen sharply compared to deaths from child and maternal malnutrition. Between 2010 and 2019, diet-related deaths rose by 16%, compared to declines of 30% for child and maternal malnutrition-related deaths. The steepest declines in child and maternal nutrition-related deaths were from vitamin A deficiency (-60%), zinc deficiency (-60%), child stunting (-48%), discontinued breastfeeding (-44%), and child underweight (-39%). Direct deaths from malnutrition have fallen by 22% over the period.

Who is vulnerable to nutrition-related deaths?

The vast majority (92%) of the 7.9 million diet-related deaths occur among adults aged over 50. In contrast, the majority (97%) of the 2.9 million child and malnutrition-related deaths occur among children under five. Direct deaths from nutritional deficiencies are more evenly spread across the life-cycle, with 39% occurring among children under five and 50% among adults over 50. Males are more vulnerable to diet-related (57% of all deaths) and child malnutrition-related (55% of all deaths). Twice as many men as women die from causes related to diets high in red meat, processed meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages, and low in whole grains. More males than females also die from low birth weight, child stunting, low breastfeeding, zinc and vitamin A deficiencies.

In contrast, females make up 55% of direct deaths from malnutrition, due to the larger numbers of young girls and elderly women who die from protein-energy malnutrition. In fact, 73% of direct deaths from this form of malnutrition are concentrated among women and children. The one area where the burden of nutrition-related deaths falls exclusively on females is iron deficiency. In addition to contributing to the deaths of an estimated 42,000 women, iron deficiency is a major cause of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) for women. Only unsafe sex is a higher behavioral risk for women aged 15-49 years, according to the GBD.

Where are the most nutrition-related deaths?

The majority of nutrition-related deaths occur in a subset of twenty countries which fall into three groups. First there are the countries where more than 80% of nutrition-related deaths are due to dietary risks, including China, Russia, USA, Ukraine, Japan, Germany, Viet Nam, Egypt, and Italy. Second are the countries where between 50 and 80% of deaths are due to dietary risks, including India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Brazil, Bangladesh, Philippines, and Mexico. Finally there are the countries where less than 50% of deaths are due to dietary risks. Instead child and material malnutrition dominates, including Nigeria, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Tanzania – all in Africa.

Countries from almost every region of the world are on this list indicating the wide spread of nutrition-related deaths. However, most diet-related deaths are in middle- and high-income countries while most child and malnutrition-related deaths and deaths from nutritional deficiencies are in low- and middle-income countries across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, due to the heavy burdens in India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and others. It is important to note that five countries are struggling with high numbers of nutrition-related deaths across all three categories – dietary risks, child and maternal malnutrition, and nutritional deficiencies – including India, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, which is a reflection of the double-burden of malnutrition across Asia.

What now?

The critical first step in reversing the global nutrition crisis is setting the right priorities. If governments, companies, and civil society can agree that action on the following issues among specific populations and countries will have the greatest impact on reducing nutrition-related deaths and disabilities, the world will be better positioned to tackle the crisis. The GBD analysis suggests that prioritizing the following five nutrition issues in the highlighted populations has the greatest potential to prevent nutrition-related deaths (in order of impact):

(1) Poor Diet: Efforts to change diets should focus on sodium reduction and increases in whole grains, nuts and seeds, and vegetables and fruits in the diets of men and women aged over 50, with a special focus on older populations in China, India, Russia, the USA, and Indonesia. The large gender gap in diet-related risks underscores the need for special efforts to improve men’s diets in these countries.

(2) Low Birth Weight: Efforts to reduce the population of babies born with low birth weight should focus on young women both before and during pregnancy in India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Bangladesh. There should also be a massive effort to improve the diets of babies born with low birth weight in these populations, especially in the first months of life. Increasing access to breast milk and breast milk supplements will be vital for this population of babies.

(3) Child Wasting: Efforts to prevent, diagnose, and treat child wasting should target children under five in India, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Pakistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo for maximum impact. To reach the children at risk of wasting as well as those currently experiencing the condition, efforts are needed to integrate wasting services with high-touch child health services – especially vaccination which reaches more children than any other health service.

(4) Protein-Energy Malnutrition: Unlike diet and child and maternal malnutrition which raise the risk of death, nutritional deficiencies are still a direct cause of death for an estimated 252,000 people. This is unacceptable. Efforts to eliminate deaths from protein-energy malnutrition should target women aged 15 to 49 and children under five in Nigeria, India, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mali, Tanzania, Chad, Angola, and Burkina Faso.

(5) Iron Deficiency: As a leading cause of disability for women of workforce age, efforts to reduce iron deficiency anemia should focus on women aged 15 to 49 and children under five in Nigeria, India, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mali, Tanzania, Chad, Angola, and Burkina Faso, Pakistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

Aligning the actions of the global health agencies responsible for nutrition and the donors who support their work with these nutrition priorities in these populations and countries, is our best bet at reducing nutrition-related deaths in the world.

Updated January 2024