PREVENT EARLY DEATH

LIFE EXPECTANCY AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

It was Amartya Sen who championed the idea that human development could be measured by increases in human life span. The basic idea is that a life cut short is a great injustice – perhaps the greatest injustice of all – and that being able to live a long life is a critical measure of development. Martha Nussbaum further underscored the value of a long life by making it the first of her “Ten Central Capabilities”: Life. Being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; not dying prematurely or before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living.

Life expectancy at birth is also the first of three measures included in the Human Development Index, which was created to emphasize that people and their capabilities should be the ultimate criteria for assessing the development of a country, not just measures of economic growth.

In recent decades, many nations have been able to extend the life of their citizens. Life expectancy at birth rose from 65 in 1990 to 71 in 2021, according to the United Nations. Increases in some low- and middle-income countries (e.g., China) were more than twice as fast as high-income countries over comparable periods.

But this global progress masks deep regional inequalities. Today, average life expectancy is 60 years in Sub-Saharan Africa, 68 years in South Asia, 73 in the Middle East and North Africa, 72 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 77 in Europe and Central Asia and 77 in North America. All 15 of the countries with life expectancy at birth below 60 years are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

There are also differences within Africa, where life expectancy ranges from 53 (Chad, Nigeria, Lesotho) to 74 in Cabo Verde. Further, as life expectancy remains below 60 in many of the HIV/AIDS-affected countries (e.g., Lesotho and Eswatini) but rises into the high 60’s in several countries in the east, the gaps in Africa are widening.

The highest performing country in the world and the “frontier” for life expectancy is Japan, where the average citizen lives to 84 years.

An outstanding analysis of the contribution of increasing life expectancy to economic growth and development, Global Health 2035, found that annual increases in life expectancy added 1.8% to annual GDP for all low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2011.

Reductions in early death trigger a range of positive development forces, including declining fertility (as more children survive, parents have fewer children), growing working-age populations (and greater productivity), rising savings rates (as people plan for longer lives), increasing foreign investment and falling healthcare costs (as populations thrive, at least in the short term before the costs of aging set in).

Global Health 2035 concludes that “this new understanding of the economic value of health improvements provides a strong rationale for improved resource allocation across sectors.” Their conclusion is clear. Nations should be investing more in health relative to other sectors and investing in ways that increase life span.

13 MILLION LIVES CUT SHORT EVERY YEAR

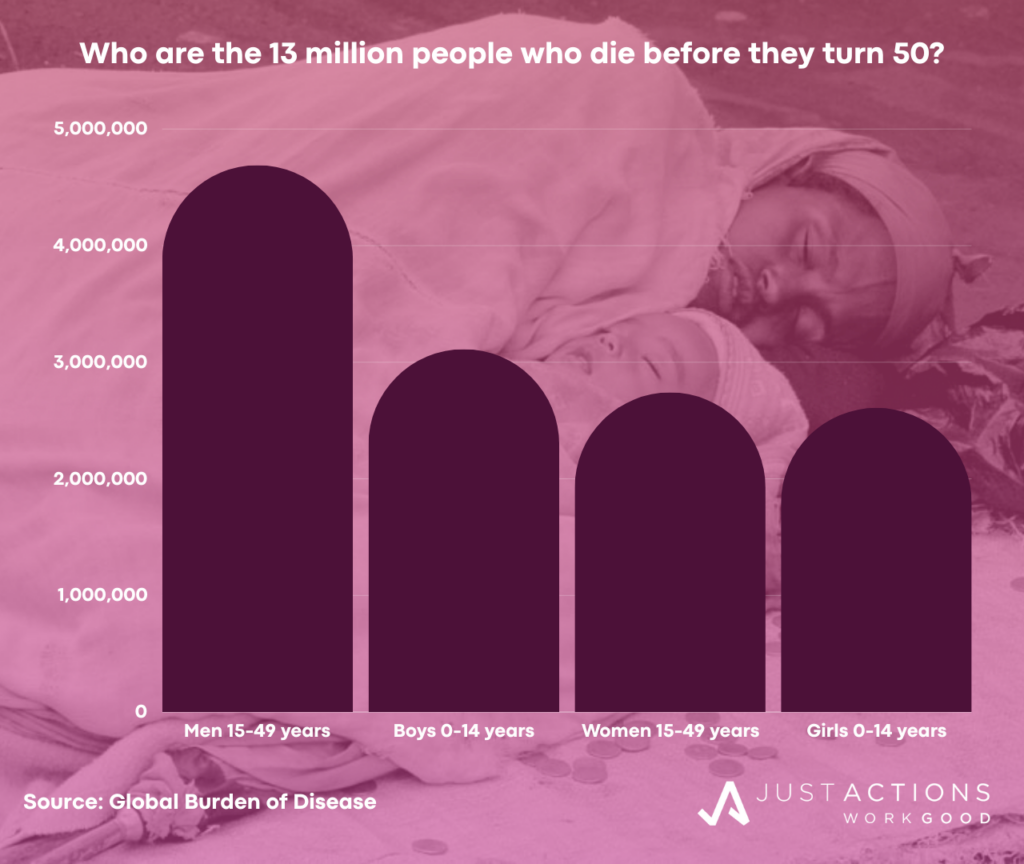

It is largely because of the spotty progress in increasing life expectancy at birth that we live in a world where an estimated 13 million people die before they turn 50 each year; including 5.7 million children under five years of age, 4.7 million adult men, and 2.7 million adult women, according to the Global Burden of Disease. There are wide gender gaps among early deaths for adults with men comprising 63% of early adult deaths, largely due to additional male deaths from road injuries and heart disease.

If we add in the estimated 1.4 million unborn females who are victims of sex selection every year (largely in China and India), the gender gap shrinks but is not eliminated. If we include female deaths from sex selection during pregnancy and the estimated 1.9 million stillbirths that occur every year we have a population of 16.3 million whose lives are cut short every year.

The majority of early deaths occur in just ten countries, including India, Nigeria, China, Pakistan, Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Brazil, the USA, Russia, and Ethiopia. Four countries – India, Nigeria, China, and Pakistan – account for 5.4 million early deaths or 41% of the global total. In many of these countries early deaths represent a large proportion of overall deaths, above the global average of 23%, and far above Japan’s 3% – the world’s best.

For example, in Nigeria, home to the world’s second-largest concentration of early deaths, 67% of all deaths occur among people under fifty. In the Democratic Republic of Congo it is 56%, in Pakistan 52% and in Ethiopia 41%.

A handful of causes account for the vast majority of early deaths, including neonatal disorders, pneumonia, road injuries, diarrhea, heart disease, HIV/AIDS, malaria, congenital defects, self-harm, and tuberculosis. The major causes of death vary by age and gender.

Children under five are much more likely to die from neonatal disorders and infectious diseases (especially pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria), while adults are more likely to die from road injuries, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS. Infectious diseases are also leading causes of death among children aged five to 14 (especially typhoid, diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria), but road injuries and drowning are also big killers.

Road injuries are the largest cause of death among 15 to 49 year-olds, followed by heart disease, HIV/AIDS, and self-harm. Other leading killers for this population include tuberculosis, cirrhosis, and stroke. The leading causes of death for men and women under 50 are similar, but road injuries, heart disease, and self-harm claim the lives of many more young men. HIV/AIDS kills more young women than men and death in pregnancy and childbirth remains a major killer for women, claiming 194,000 lives.

The leading risk factors for death before 50 years include low birth weight, short gestation (preterm birth), child wasting, high blood pressure, alcohol use, household air pollution, unsafe sex, unsafe water, outdoor air pollution, and high body mass.

Leading risk factors vary by geography and gender. For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa, low birth weight, child wasting, short gestation, unsafe sex, unsafe water, and household air pollution are leading risk factors for early death. But in South Asia, low birth weight, short gestation, child wasting, high blood pressure, and household air pollution are the top five risk factors.

The leading risk factors for early death among females are low birth weight, short gestation, child wasting, unsafe sex, and high body mass. In contrast, low birth weight, short gestation, alcohol, high blood pressure and smoking are the leading risks for early death among males.

REDUCING EARLY DEATH: A NEW DEVELOPMENT PRIORITY

Many of the 13 million early deaths are preventable with low cost, high impact interventions including contraception, vaccination, devices (e.g., condoms, malaria bed nets, rapid diagnostic tests, pulse oximetry etc.), therapeutic foods and supplements, and medicines (e.g., antiretrovirals, artemisinin-based combination therapies, oral rehydration salts/zinc tablets, antibiotics and oxygen). Others require higher-cost interventions, especially diagnosing and treating heart disease, preventing newborn deaths and suicide.

Substantial behavior changes relating to diet, alcohol and tobacco use, sexual practices and cooking norms are required to reduce the risks of early death. Reducing the risks of air pollution will ultimately require changes to industrial, agricultural, transport and urban policies and practices, and are likely to be very challenging in economies that are transitioning from low- to middle-income status. Deaths from road injuries are projected to increase rapidly in countries with weak road infrastructure and limited transport safety policies.

The evidence suggests that where investments in health interventions are made alongside investments to improve the education of girls and women of reproductive age, large gains are possible. Fully half of the reduction in child deaths since 1970 has been due to increases in the education of women of reproductive age, according to a study by Chris Murray and colleagues. Women’s education was also found to be critical to child mortality declines, alongside access to clean water and sanitation, poverty reduction, and economic growth, according to a World Health Organization study.

Accordingly, all countries should make reducing early deaths (<50 years) the focus of their national health goals by maintaining early deaths at <20% of all deaths by 2025 and <15% by 2030. For countries already at these levels, targets of <15% and <7% should be set with Japan’s rate of 3% as the ultimate goal. This focus on reducing early deaths is supported by a recent Lancet study which concluded that “reducing premature deaths is a flexible target that can be pursued in different ways in different countries, according to their mortality patterns and resources,” and by the Copenhagen Consensus, which has consistently argued that investing in increasing lifespans is the most cost-effective development investment in the world today.

National health plans and programs should target the leading causes of early death in their respective countries and invest in the most cost-effective solutions targeted to the most vulnerable populations. In many low- and middle-income countries infectious diseases, newborn deaths, and road injuries will dominate the causes of early death, while in higher-income countries non-communicable diseases, injuries, and self-harm will dominate. In countries where stillbirths and sex selection are major challenges, reductions in pregnancy termination related to sex selection and preventing stillbirth should be national health priorities.

In addition to investing to improve the diagnosis and treatment of the leading causes of early death, governments and other stakeholders should invest heavily in prevention by reducing population exposure to the major risk factors, especially low birth weight, short gestation, child wasting, unsafe sex, alcohol use, smoking, high blood pressure, air pollution, and poor diet.

Finally, we need to invest in solutions that go beyond a single disease or intervention to better integrate the financing and delivery of the products and services with the greatest impact on reducing risk and death among the populations where early deaths are concentrated.

We need to aim for the vision outlined by Jim Kim, Paul Farmer and Michael Porter in “Redefining Global Health Care Delivery”, where the creation of “patient value” is the endgame because this is ultimately what will drive people to seek healthcare enabling population-wide health improvements and the achievement of global health goals.

Solutions also need also to address the underlying political, economic, and social causes of early death. As the majority of early deaths occur in countries where people struggle on low incomes, where governments are often dysfunctional, where markets are not strong, and where women are disempowered, specific health interventions need to be delivered in the context of broader reforms to encourage economic growth and rising incomes, to build stronger democracies and markets, and to empower women.

REFRAMING GLOBAL HEALTH PRIORITIES TO FOCUS ON EARLY DEATH

The United Nations (UN), its agencies, and development partners should reinforce this focus on reducing early deaths under the Sustainable Development Goals, and target national and international health investments to the leading causes and risk factors associated with early death.

The UN should encourage and incentivize, where necessary, country investments in the highest-impact, most cost-effective interventions that can prevent, diagnose, and treat the leading causes of early death and ameliorate the risk factors associated with them. The UN should support national prioritization of the populations with the largest burdens of early deaths.

To model the much needed integration in the financing and delivery of the products and services with the greatest potential to reduce early deaths, the UN, its agencies, and partners should establish flagship multi-sector initiatives in each of the leading causes of early death (e.g., infectious disease killers, road injuries, heart disease, newborn causes, and self-harm), and risk factors (e.g., low birth weight, child wasting, unsafe sex, alcohol and tobacco use, air pollution, and diet).

Integrated financing, policy development, and program delivery will accelerate reductions in early deaths and put population health on a trajectory of convergence with the highest performing countries. These flagship initiatives should disproportionately benefit the populations with the largest concentrations of early deaths in each of the causes/risks.

A final note. This analysis has focused only on early death and not on disability. Behind the statistic of 13 million early deaths lie hundreds of millions of episodes of sickness, many of which leave children and young adults with lifelong disabilities.

Action to prevent early deaths and to reduce the risk factors associated with them will also reduce this heavy burden of sickness and disability that prevents so many from reaching their full potentials and acts as a barrier to national economic and social development.

Updated January 2024