REVERSE INEQUALITY

INEQUALITY IS ON THE MARCH

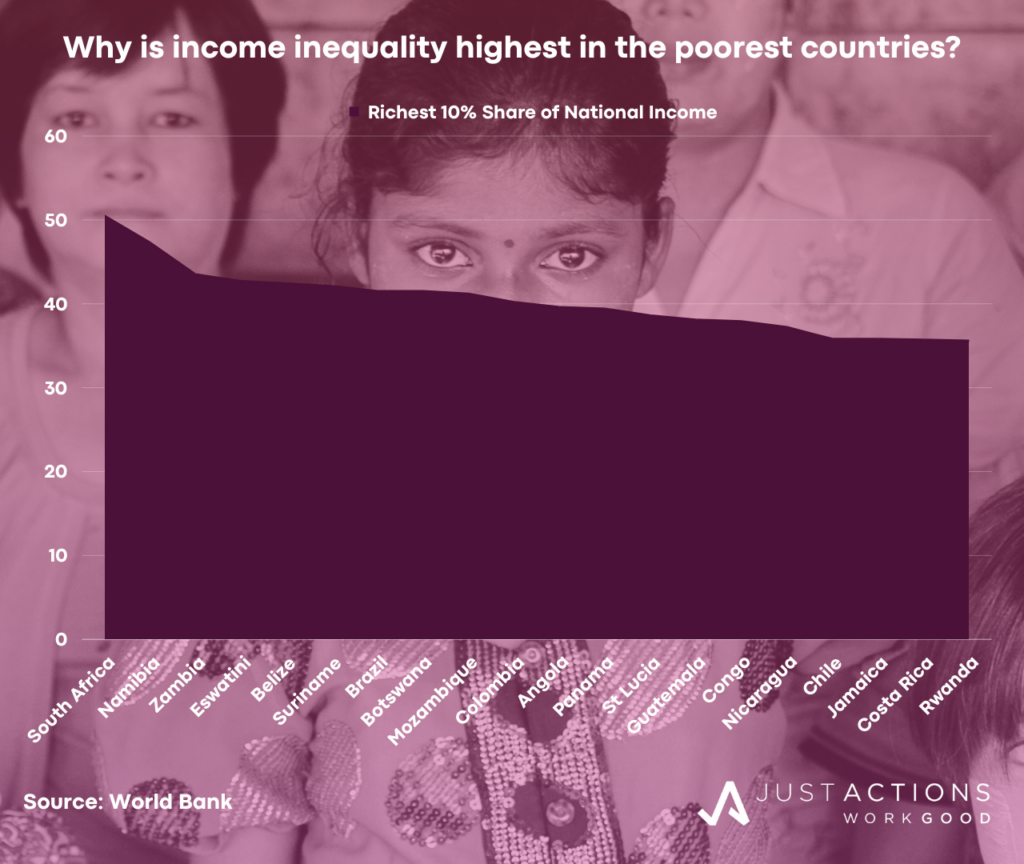

Income inequality is high and rising in many countries as the benefits of economic growth are captured by wealthy minorities. The official measure of income inequality, the Gini Index, records high rates of income inequality for many of the world’s countries. With perfect inequality at 100, the highest levels of income inequality are actually found in lower income countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, where all 20 of the world’s most unequal countries are found. In all of these countries the richest 10% of households own 33% or more of national income, according to the World Bank.

Income inequality is also rising in many high-income countries. The OECD reports that inequality has risen in 15 of 34 OECD countries, including Denmark, Estonia, France, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the USA, causing the overall OECD average to rise. Income inequality is also rising in many countries across sub-Saharan Africa, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), but is declining in most Latin American countries according to the World Bank.

While low levels of income inequality are no guarantee of thriving societies, there may be a relationship between more equal societies and human development. Seventeen of the 20 countries with very low income inequality (i.e., Gini scores below 30) score highly on the Human Development Index, including Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark, Iceland, and Norway. The only highly equal societies scoring poorly on the Human Development Index are Timor-Leste, Iraq, and Kyrgyzstan.

INEQUALITY AS A THREAT TO DEVELOPMENT

Although there is great debate about the impact of inequality on economic growth, and vice versa, there is a growing consensus that inequality is a problem when it results in very large populations trapped in poverty with limited or no opportunities for social mobility, which can impede long-term economic growth. Focusing on high income countries, several leading economists argue that continued high rates of income inequality are a threat to sustained economic growth, political and social stability, and democratic values and institutions. In the USA, which is the most unequal of the high income nations, Joseph Stiglitz argues that inequality carries a high price tag, including economic instability and high social costs (i.e. the costs of incarceration) that threaten growth. Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson add low life expectancy, obesity, and poor educational outcomes to the costs of inequality.

Focusing on the UK, Anthony Atkinson says that over time inequality undermines equality of opportunity and social mobility as wealthy minorities pass unfair advantages to successive generations. In an exhaustive study which revealed that USA income inequality has risen to the same level as the early 1900s, Thomas Piketty concludes that inequality is a threat to democracy because it, “radically undermines the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based.” If the arguments against income inequality in high income countries focus on threats to development already achieved, the arguments against income inequality in developing countries charge that inequality inhibits much-needed development gains. Martin Ravallion has concluded, quite simply, that “inequality is bad for the poor,” and François Bourguignon has said that too much inequality in low income countries can be a brake on growth resulting in institutions that are unfavorable to development and to large populations being excluded, especially from access to credit and quality education. He has championed the concept of “inclusive growth” in these countries.

Michael Kremer and Eric Maskin have lent weight to this concept by showing that in poor countries it is often the relatively skilled workers who can take advantage of new job opportunities that result from increased trade, while those with less relevant skills (i.e. agricultural laborers) fall further behind. Increased economic growth under these circumstances can actually contribute to income inequality in low income countries.

In poor countries the price of inequality can be measured in life and death. Data from both UNICEF and the World Bank show that the richest 20% of households enjoy much greater access to healthcare and experience much lower rates of early death, especially among children, as a result. Studies across several countries have also found evidence of ”death clustering” with a majority of child deaths “clustering” in a minority of extremely poor and disempowered families. Monica das Gupta’s important study in rural India found that 62% of child deaths clustered to just 13% of families, and Anthony Klouda’s study of northern Nigeria found an even higher rate – 80% of child deaths concentrated in 20% of households. Over time, large populations of disenfranchised people can threaten peace and security. The World Economic Forum has constantly ranked “severe income disparity” among the highest risks facing the planet over the last decade.

ENSHRINING THE CONCEPT OF “SHARED PROSPERITY”

To shift the democratic conversation and government policy making towards reversing and reducing income inequality, especially in the countries where it is both high and rising, countries should embrace the World’s Bank’s “shared prosperity” agenda and set a new target to increase the share of national income owned by the bottom 40% to at least 20% by 2025, and to at least 25% by 2030.

Strategies to achieve this goal should include educational investments, jobs growth, and taxation and social policies that disproportionately benefit children and youth from the bottom 40% of households. Countries should introduce a progressive tax on extremely high incomes, wealth, and the intergenerational transfer of wealth to finance investments in education and job creation that disproportionately benefit the bottom 40%. The overriding objective should be to strengthen the capacities of those on the lowest incomes to contribute to, and capture the benefits of, economic growth and to finance these investments in such a way that income and wealth inequality are reduced.

The United Nations (UN), its agencies, and development partners should support both national efforts to reduce income and wealth inequality building upon Sustainable Development Goal 10.1 (“progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40% of the population at a rate higher than the national average”). In implementing this goal, the UN should measure and report national progress on increasing the share of the bottom 40% to 25% of national income by 2030.

The UN should also ensure that development assistance, especially to low and middle income countries with high inequality, disproportionately benefits the bottom 40% and leverages fiscal, wage, and social policy reforms that contribute to greater income equality.

A Final Note. While inequality within many countries is rising, global inequality between countries has actually fallen, due to the extraordinary economic rise of a small number of counties like China and India, as Branko Milanovic has pointed out. But it should be possible to improve both national and global income equality simultaneously with an intense, targeted and even coordinated focus on reducing income inequality among the large population countries with high rates of income inequality, including China, the USA, Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria, Russia, Mexico, the Philippines, Türkiye, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Achieving greater equality of incomes both within countries and between countries is the ultimate goal of a truly global economic growth and human development agenda.

Updated January 2024