Should we reward women who breastfeed?

Breastfeeding is one of the jewels in the crown of child health, according to public health authorities. The release of the first Lancet Series on breastfeeding in 2016 found that not only could breastfeeding save the lives of 820,000 babies and 20,000 women each year, but it could also cut healthcare costs by hundreds of millions of dollars. The biggest winners would be the littlest ones – babies under one month old – because breastmilk is often the only “medicine” available. In fact the Lancet study describes breastmilk as, “probably the most specific, personalised medicine that (baby) is likely to receive, given at a time when gene expression is being fine-tuned for life.”

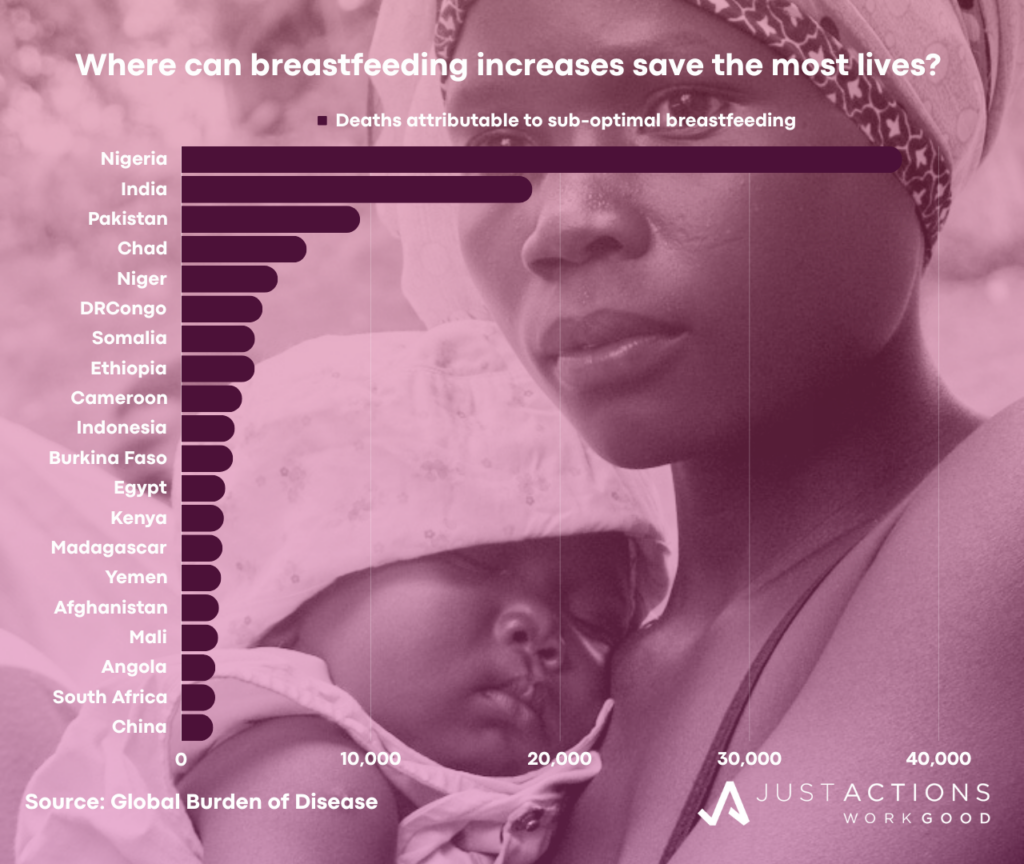

The Global Burden of Disease is more circumspect, estimating that “suboptimal breastfeeding,” defined as non-exclusive in the first six months and discontinued by twelve months of age is a risk factor in 146,300 child deaths, Twenty countries account for the vast majority of these deaths (see chart) and almost all breastfeeding-related deaths occur in the first year of life, where 74% of all deaths among children under five now concentrate. So why do the majority of women in the world opt not to exclusively breastfeed their babies? Globally, just 46% of newborns are breastfed within an hour of birth and 48% breastfed exclusively for the recommended six months, according to UNICEF. While rates are higher in many low- and middle-income countries, and especially across Africa, only 45 countries have achieved the global breastfeeding target of 50% exclusive breastfeeding for babies under six months of age by 2025.

The high and rising costs of breastfeeding

Why are breastfeeding rates so low and progress so slow? Unlike most health interventions, breastmilk doesn’t cost money to produce or purchase (aside from the costs of keeping mother well-nourished). And for the most part, breastfeeding is not vulnerable to typical supply or demand issues as most women can produce breastmilk after birth and most babies will demand it. There are important exceptions to this for mothers who are malnourished themselves, or who are suffering physical and or mental illnesses. Logistics are also pretty straightforward, as breastmilk is manufactured and delivered right on baby’s doorstep, assuming mothers and babies can stay close.

But there is one crucial factor the world hasn’t paid enough attention to – the high and, in many countries, rising costs of breastfeeding – which currently fall on mothers, and disproportionately on mothers with low incomes, especially those living in the twenty countries with breastfeeding-related deaths occur. First and foremost, there are the financial costs of wages lost because it is just so hard to work and breastfeed ten to twelve times a day, even with an understanding employer. These costs are felt most acutely by women on low incomes who must work. For these women, there is no “choice” to breastfeed when going back to work is a matter of family survival.

There are also the opportunity costs of losing up to five hours every day nursing when you could be pursuing other activities. This cost also falls disproportionately on low-income mothers as they are more likely to have large, often extended, households to manage and several children to raise, without help from others. The social costs of restricted mobility can also be high when breastfeeding mothers need to be physically attached to their babies for significant parts of the day, especially in settings where there is limited or no access to breast pumps and other technologies that enable nursing mothers to be away from their babies for lengthy periods. Once again, mothers on low incomes are least likely to have access to supportive technologies, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Finally, the pain and suffering costs of breastfeeding can be extreme and are amplified when women cannot access support from qualified lactation specialists. Not surprisingly, lactation support is often unavailable for women living in low-income households, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Offsetting the costs

But what if the women who experience the highest breastfeeding costs – women on low incomes – were actually compensated for these costs? What if these mothers received extra time, cash, products or services, or a mixture of all four when they breastfed? This is not a new idea, but it is the subject of some recent controversy – just take a look at the reactions to Courtney Jung’s Lactivism and a University of Sheffield trial in the UK that paid women on very low incomes to breastfeed exclusively.

Controversies aside, incentivizing the women who face the highest costs to breastfeeding but whose children also stand to gain the greatest benefits is good public policy. These are the women who should be first in line for paid maternity leave so they can breastfeed at home, and if they choose instead to return to work after baby is born, they should be first in line for paid work breaks to breastfeed if baby is in care nearby or to pump. They should have preferential access to quality, affordable breast pumps and to other breastfeeding supportive technologies.

We also know from decades of experimentation that conditional cash and non-cash incentives provided directly to women, especially those living in low- and middle-income countries, do influence healthier behaviors. Why not experiment further and at large scale with paying women who breastfeed where the costs of not doing so are very high and fall disproportionately on the most vulnerable babies? And if cash is not the solution, why not try non-cash rewards such as products (e.g., nutritious food vouchers for the family) and/or services (e.g., free family health care).

Each year an estimated 140 million women will face the decision whether to breastfeed or not. If rewards can increase breastfeeding rates among the populations of babies most exposed to the health risks associated with sub-optimal breastfeeding and do not penalize mothers on low-incomes who cannot breastfeed, they deserve to be a standard part of breastfeeding policies and programs, especially in countries struggling with high rates of child deaths. It is highly likely that the costs of funding rewards like these would be more than fully offset by savings to the health system and returns to society from healthier babies. And as every additional dollar given to mothers benefits the health and education of their families, cash and in-kind rewards for breastfeeding may actually end up delivering a double benefit that goes well beyond the immediate health gains for the breastfed baby.

The Sustainable Development Goal deadline of 2000 is fast approaching. A new target of 70% exclusive breastfeeding by 2030 has been proposed by the Global Breastfeeding Collective. So let’s start experimenting with different approaches that compensate breastfeeding mothers for the service they are providing to their families, to their communities and ultimately, to the world, and let’s make sure the mothers who face the highest breastfeeding costs and forfeit the greatest benefits are first in line for extra support.

Updated January 2024