How do so many smart girls become such powerless women?

Girls are increasingly outperforming boys at all levels of education in a majority of countries, and yet women are still the vast majority of the world’s poor and disempowered. How do so many smart girls grow up to become such powerless women? Most girls, no matter how highly educated they are or where they live in the world, will encounter three formidable barriers to realizing their full potentials – marriage, motherhood, and masculine work norms.

The “3Ms” operate together to dramatically reduce the time a woman has available for paid work, to inhibit her chances of success when she does work for pay, and to make the decision to forgo paid work, economic independence, and public influence the easier one. So powerful are these three interacting forces that without their deactivation the educational gains that girls make can never be fully realized in adulthood anywhere in the world, and no country can fully capture the potential gains from women’s empowerment.

How does the superior educational performance of girls contrast with poverty, vulnerability, and powerlessness for so many of the world’s women?

Superior educational performance

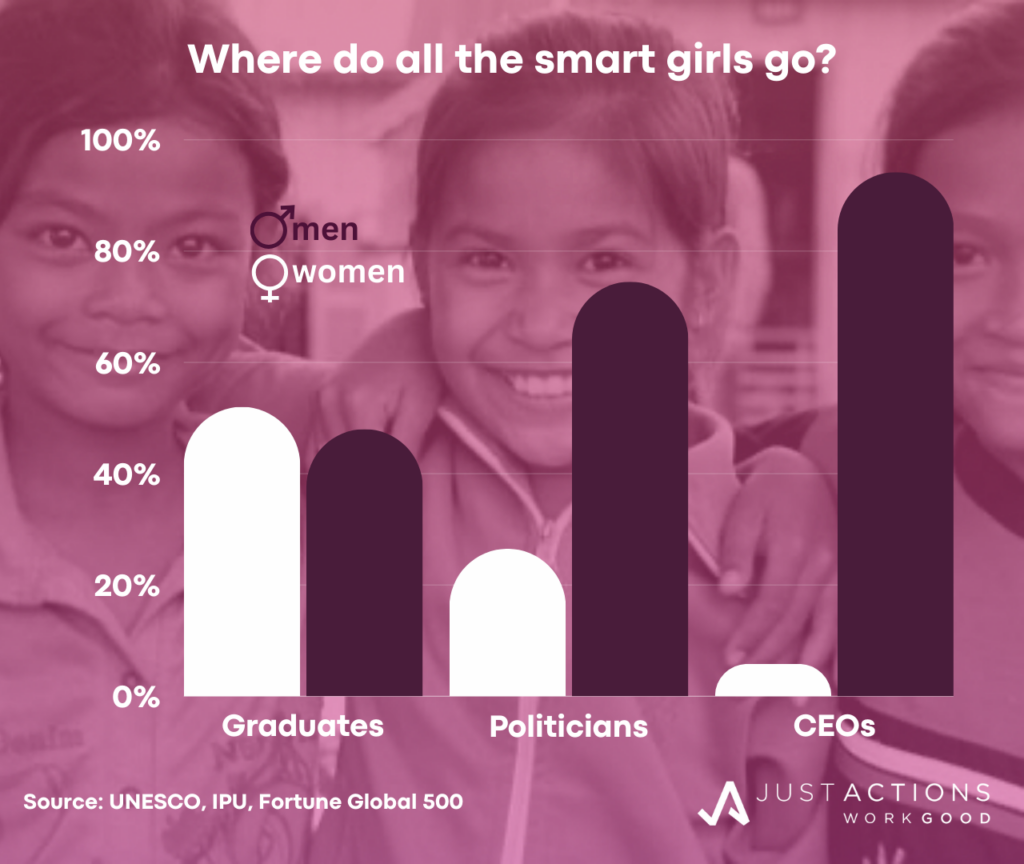

Globally, there are now almost as many girls as boys enrolled in primary and secondary schools, and girls are more likely than boys to be enrolled in university. For every 100 boys in primary and secondary school there are 99.7 girls, while for every 100 men enrolled in university there are 113 women, according to UNESCO.

A diverse group of high-, middle-, and low-income countries now enroll more women than men in primary, secondary, and university education, including the United Kingdom, France, Denmark, Argentina, China, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Mexico, Honduras, and Ecuador.Other countries like the USA, Japan, Nepal, Iran, and Rwanda are well on their way to crossing this threshold. In several countries it has taken just ten years for women to bypass men in the attainment of educational qualifications.

For the first time in the history of the world, we can contemplate a planet where girls are more educated than boys. But here’s the real question. Will these girls be able to use their early educational advantage to transform their lives as women and shape the future of the planet?

Poverty and vulnerability

They certainly haven’t yet. Despite rapid educational advances by girls, most of the world’s poor and powerless are still female. 55% of the world’s 3 billion women aged over 15 are not employed (in contrast to just 32% of men), and this rate has actually increased over the last decade, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO).

These 1.7 billion “non-employed” women are dependent on others, typically male family members, for survival. Most live in low- and middle- income countries and typically work very long hours in unpaid family work. Should they lose their connection to a male earner through death or divorce, they are at high risk of life-threatening poverty.

In almost every country in the world the 45% of women who do work for pay earn less than their male peers, and are more likely to work on the peripheries of the labor market in the less profitable and informal sectors, according to the World Bank.

Women’s lower levels of employment and earnings contribute to higher rates of poverty and greater vulnerability to specific health problems and violence. More than four out of 10 women in South Asia and an astounding two out of three women in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa experience violence, most of it from an intimate partner, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Powerlessness

Lack of access to employment is also a root cause of the relative powerlessness or very low representation of women in seats of power. There are just 9 out of 152 women heads of state and 13 out of 193 heads of government, and women hold just 26% of seats in Parliaments across countries, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

In the corporate world, it is even worse. Women lead just 29 (6%) of the top 500 companies on the Fortune Global 500 and hold 21% of board seats globally, according to an MSCI study. These rates are proving stubbornly resistant to change. If the pace doesn’t quicken, it will take until 2045 to reach 50%.

In another influential sector of society the situation improves slightly, with women leading 48 (24%) of the world’s top 200 universities, according to Times Higher Education. However, religious leadership is overwhelmingly the domain of men, with just four women among the world’s most powerful religious leaders.

In all parts of the world the vast majority of girls do not grow up to influence the decisions or the institutions that determine the quality of their lives. As women they still remain relatively powerless to shape the world in which they live and where the future generations they bear grow up.

The “3Ms” – marriage, motherhood, and masculine work norms

Why are so many smart girls not being rewarded with the pay and positions of power that their increasingly superior educational performance warrants?

At the most basic level the villain is time – a switch that is triggered by marriage and fully flipped by motherhood. Women spend at least twice as much time as men on unpaid caring and housework, and when paid work is taken into account, women work longer hours than men across all regions, according to the United Nations (UN).

Lack of access to paid parental leave, affordable childcare, and home-help exacerbates this time crunch, forcing some level of “disengagement” from the paid workforce by all but the minority of women earning very high incomes. Disengagement can range from working fewer hours, to opting for lower paid, less demanding jobs, to passing on promotions, to withdrawing entirely for a period of years or even for a lifetime.

This disengagement shows up in the large differences in employment and earnings between men and women with children. There is a 21 percentage point gap between the proportion of married men and women with children under 18 who are in the US labor force, compared to a nine percentage point gap for those with no children, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

With respect to weekly earnings, fathers with dependent children in the US earn on average $US298 more than mothers – the so-called Motherhood Pay Penalty – compared to a $US123 weekly gap for men and women with no dependent children, according to the BLS. The ILO reports that motherhood pay gaps are even higher in lower income countries.

And when it comes to positions of power, mothers are dramatically underrepresented, holding just 1 in 10 of the top jobs in the US in stark contrast to fathers who hold 8 out of 10 top jobs, according to the Motherhood + Public Power Index.

Masculine work norms are the underlying reason marriage and motherhood carry such heavy penalties for women and create an impossible “choice” between paid work and unpaid family work. Norms can range from complete restrictions on women doing certain jobs to expectations of long hours at work, constant travel, and 24/7 availability that are completely incompatible with raising children. The fact that masculine work norms are most powerful in the sectors that pay the highest wages (e.g., finance and technology) further reinforces occupational segregation and the gender pay gap.

The social and economic costs to women, to communities, and to entire nations of marriage, motherhood, and masculine work norms, and the lifetime disempowerment and separation of women from public life that these three forces feed are catastrophic and immeasurable.

Deactivating the “3Ms” – a three-step plan

Almost all societies throughout history have failed to finance the costs of family formation and parenthood efficiently and equitably. The vast majority of costs are born privately, by families, but especially by women who continue to pay unacceptably high economic, social, and political costs for the unfair distribution of unpaid family work. At the end of the day, this denial of full participation to half of the planet’s population restricts national economic growth and human development.

To date, many women have been responding to the triple-threat of marriage, motherhood, and masculine work norms by using the few levers in their control – by delaying marriage or by not marrying at all, and by having fewer children or no children at all, a trend well documented by Rebecca Traister in “All the Single Ladies.”

Unable to change mainstream workplaces many women are instead attempting to control their own hours of work and daily schedules by opting for part-time work, by starting their own businesses, by job sharing with other mothers, and/or by working from home.

However, each of these options carry heavy trade-offs and fall short of what mothers truly want, which is to find jobs that pay well and allow enough flexible time for good parenting. What is needed are new models of family formation and work that distribute the costs of unpaid care fairly – both within families and across society – and incentives for governments and companies to experiment with them.

1. Promoting alternatives to marriage

First, women need more choices when it comes to forming a family – choices that are fully compatible with female financial independence and public influence. If the role of wife comes with pressure to perform more work at home for no pay leaving less time for paid work, women should be encouraged and supported to pursue other options for family formation.

Alternative family models might include cohabitation without marriage, maintaining separate households, multi-family living arrangements, and new forms of short-term contractual partnership which do not carry the financial risks of marriage and divorce.

For societies where marriage, and particularly early marriage, is still the cultural norm, outlawing marriage before the age of 21, dismantling discriminatory family laws and practices associated with marriage (e.g., female genital cutting, dowry, polygamy), as well as increasing access to divorce are critical first steps. Incentives to delay marriage in the form of education subsidies to girls and boys conditional on maintaining single status should be on the table.

Most importantly in all societies, future generations of young women should feel that choosing not to marry or to raise children without marriage are both fully acceptable choices. They should be supported by public policies that do not incentivize marriage through the tax and/or transfer systems and which instead encourage and reward delayed marriage.

Governments should consider setting explicit national goals to increase the age of first marriage and childbirth to 30 by 2030 and ensure that all women have full access to modern contraception.

Women choosing to have children should consider limiting their family size to the number of children that they can financially support should they find themselves without a partner or husband. The desperate financial situation so many women are plunged into following partner death, divorce, or separation is the cause of so much female and child poverty. Limiting family size is an insurance policy against future sole parent poverty.

2. Eliminating the Motherhood Pay Penalty

Second, the Motherhood Pay Penalty must be eliminated so that women with dependent children do not face employment and/or earnings barriers relative to fathers. The primary strategy to achieve this goal should be based on creating what Harvard economist Claudia Goldin calls “temporal flexibility” and what Anne-Marie Slaughter calls “deep flexibility” in employment, by allowing workers with caring responsibilities flexibility in three fundamental areas – when they work, where they work, and how they work.

Flexibility should be at its most elastic when caring responsibilities peak over the life-cycle (e.g., in the years following the birth of a child and when aging parents become ill) and extended, paid family leave should be standard practice during these periods.

It should also be possible for employees to work during these intensive periods, if they choose, with control over their hours and location of work, assisted by the use of technology (e.g., video conferencing in lieu of travel).

At all other times there should be negotiated access for workers with family responsibilities to flexible weekly work hours, location, and method (e.g., use of technology, job sharing) of work. These flexible work arrangements should be gender-blind, meaning female and male employees with caring responsibilities can take equal advantage of them.

To finance flexibility, new schemes will need to be created and could include “caring insurance” where employees and employers both contribute to savings pools early in a worker’s career that can be drawn down as caring responsibilities peak. Governments could incentivize such schemes by offering corporate and personal tax incentives.

For workers on low incomes, governments will need to play a greater role and existing programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit could be transformed to facilitate paid leave for workers with caring responsibilities.

Most importantly, all governments should explicitly recognize the Motherhood Pay Penalty as a major barrier to the achievement of gender pay parity and set a new target of closing the gap by 2030.

3. Creating gender-neutral work norms

Third, the workplace must be transformed so that workers with caring responsibilities do not face barriers to entry or promotion. Three fundamental reforms should be on the table: 1) adoption of technological innovations that reduce the need for face-to-face interaction, constant travel, and 24/7 availability to work and reduce the burden of caring at home, 2) uptake of evidence-based policies to de-bias hiring and promotion based on the latest behavioral insights research, and 3) unleashing of women’s substantial and increasing leverage as both employees and consumers to pressure employers to remove barriers to women’s advancement at work or suffer financial consequences.

The world is poised on the edge of another technological revolution with artificial intelligence, robotics, virtual reality, and a host of other technologies transforming work. Can we harness these innovations to build workplaces that disrupt the old model of the “ideal worker” and build homes that don’t require long hours of unpaid maintenance?

If these innovations can be used to further blur the boundaries between work and home, improving productivity and reducing costs, the businesses that embrace them will have a clear competitive advantage.

And let’s not forget school and the time costs of caring for children. Aligning the school day with the work day (8:00am to 6:00pm), providing educational after-school programs, nutritious school meals, and affordable, quality Summer-school programs are all good places to start.

A vast literature now exists on how to “de-bias” hiring and promotion summarized brilliantly by Iris Bohnet in “What Works, Gender Equality By Design.” All employers should embrace the new tools at their disposal to make better decisions, including recruitment processes that “anonymize” applicants making it much harder for recruiters to pick those who “look and/or sound the part.”

Finally, women need to be aware of their considerable educational advantages in the labor market and their increasing purchasing power and vote with their feet by targeting companies that offer deep flexibility and where women hold half of all management and board seats.

We need to do much more than educate girls

To return to our original question – how do so many smart girls become such powerless women – it’s clear that we need to do so much more than educate girls if we expect to improve women’s lives. We need to disentangle and deactivate the interconnected obstacles – marriage, motherhood, and masculine work norms – that prevent girls from reaping the full rewards of their education, and offer our daughters paths through life where family fulfillment and the special joys of motherhood do not come at the price of economic success, power, and influence. Whoever reaches out and opens the doors of opportunity to these women will reap seismic rewards and multi-generational returns. The most potent force for the next wave of human development lies dormant – the 56% of the world’s women who are not in paid work and the many more who are underplaying their hands, locked out of positions of power and influence.

Updated January 2024