ESTABLISH NEW WORK NORMS

THE MOTHERHOOD PAY PENALTY

There is a large wage penalty for women with children relative to other women and relative to men with children. Mothers earn between 15% and 40% less than women without children across low-, middle-, and high-income countries, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Women with two and especially three children experience larger wage penalties, especially in high-income countries, as additional daughters in low- and middle-income countries often help with household and caring tasks enabling mothers to work for pay. But wage gaps are largest when mother incomes are measured against father incomes. In fact, the gap between mothers and fathers with dependent children is the largest gender wage gap of all.

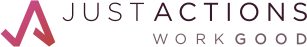

In the USA, in 2021 median weekly earnings for mothers with children under 18 years were $US301 a week lower than the median for fathers with dependent children ($US939 vs $US1,240), according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This means mothers with dependent children earned 24% less than father each week. This has hardly changed since 2010 when mothers earned 27% less than fathers.Put another way, a USA study by Michelle Budig found that mothers earn 76 cents to a father’s dollar and that mothers on the lowest incomes experience the largest pay penalties. Budig concluded that, “the women who least can afford it pay the largest proportionate penalty for motherhood.”

The motherhood pay penalty mounts over a lifetime. The lifetime earnings of mothers with one child are 28% lower than the earnings of childless women, and each additional child lowers lifetime earnings by another 3%, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. This same study found that mothers with one child receive 16% less in social security benefits than non-mothers, and each additional child reduces benefits by a further 2%. As a result of the motherhood pay penalty, poverty is higher than it would be, our workplaces are not as productive as they might be, and economic growth is not as strong as it could be.

In the USA, 30% of female-headed families live below the poverty line and have five times the poverty rate of married couple families, according to a Pew Research Center study. With so many mothers unable to fully engage in the labor market, workplaces cannot attract and retain the best talent but have to draw from a limited pool of potential employees who can offer uninterrupted labor over long periods of time. As a result, economic growth is compromised as too many women with caring responsibilities are prevented from fully engaging in the labor force. For example, in the USA, both female labor force participation (56%) and the proportion of the labor force who are women (46%) have declined in the last decade. Reducing the motherhood pay penalty is a strategy that can simultaneously reduce in-country poverty and inequality, increase labor market productivity, and national economic growth.

Reducing the motherhood pay penalty is also necessary if countries are to reap the full returns on their substantial investments in girls’ education. As Ricardo Hausmann concluded following his 40 country study of gender gaps in education, “education is not a silver bullet – it is one important aspect of empowering women, but making the labor market compatible with marriage and motherhood remains a task to be completed in many countries.”

Further, groundbreaking research by Kathleen McGinn, Mayra Ruiz Castro and Elizabeth Long Lingo found that daughters of employed mothers across 24 countries are more likely to be employed and earn higher wages than women whose mothers were home full-time. And sons of employed mothers spend more time caring for family members than men whose mothers stayed home full-time. The authors conclude that higher mother employment could gradually erode gender inequality in homes and labor markets over time.

MASCULINE WORK NORMS

Fundamentally, the motherhood pay penalty is a perverse outcome of prevailing work norms in most of the world’s occupations that disproportionately reward workers who can spend large amounts of time on the job uninterrupted by other responsibilities, in locations determined by employers, and maintain that work pattern over decades. The benefits for workers who can provide this type of “uninterrupted labor” include more job opportunities, higher pay, and often public influence, while the costs for those who cannot conform to this model of the “ideal worker” include lower labor force participation, reduced wages, and a distinct lack of public power.

As caring responsibilities are one of the main reasons many workers, typically mothers, cannot emulate these work norms the winners and losers fall along gender lines. Prevailing work norms are “masculine” because they largely serve the interests of male workers. Masculine work norms should disappear when half of all workplaces are no longer “masculine”; that is when workplaces are half female. But in most of the countries that are close to a 50% female workforce this has not happened (the Nordic countries are exceptions). Women have been streaming into workplaces since the 1960s and have almost achieved parity with male workers in a majority of countries but there has been no global transformation in work norms.

In fact, as Joan Williams has documented, bias against mothers is now the strongest form of gender bias at work with mothers less likely to be hired, promoted, and offered salaries commensurate with their childless peers. Perhaps as long as the vast majority of senior managers, board directors, CEOs, and government leaders are men, masculine work norms will dominate. Eight of every ten senior managers, Board directors, CEOs, and government representatives in the USA are male according to the Center for American Progress.

Even lower rates of representation by women in powerful positions are found in many of the lower income countries where the costs of exclusion from the labor market are particularly high for mothers, according to the Global Gender Gap Report. The underside of masculine work norms are household care norms. The interaction of the two is the underlying reason why so many women face a pernicious “choice” between paid work and family work. In all societies mothers are still responsible for the majority of family work and in several countries they perform both the majority of family and market work, according to the World Bank.

The fact that family work is unpaid has meant that mothers have been excluded from the economic system and placed in a very precarious economic position, as Marilyn Waring argued so powerfully. For mothers with no connection to the labor market poverty is a constant reality, while for mothers whose connection to the labor market is tenuous (i.e., through a male partner) poverty is a constant threat and many mothers become poor when marriages dissolve. Mothers who are fully engaged in the labor market live with the constant burden of overwork, only half of which is paid. In short, the interaction of masculine work norms and household care norms is the reason most women with children currently cannot play an equal role in the labor market, and why most men with children do not play an equal role in family life.

THE IMPORTANCE OF “TEMPORAL FLEXIBILITY”

To encourage all nations to create the conditions for new work norms to flourish that do not penalize workers with caring responsibilities, countries should set a new target of reducing the motherhood pay penalty by 50% by 2025 and eliminating it by 2030. The primary strategy to achieve this goal should be based on creating what Harvard economist Claudia Goldin calls “temporal flexibility” in employment, by allowing workers with caring responsibilities flexibility in three fundamental areas – when they work, where they work and how they work.

Flexibility should be at its most elastic when caring responsibilities peak over the lifecycle (e.g., following the birth of a child or when family members or aging parents become ill) and extended family leave should be standard practice during these periods. It should also be possible for employees to work during these intensive leave periods, if they choose, with control over their hours and location of work, and the use of technology (e.g., video conferencing in lieu of travel, etc.). At all other times, there should be negotiated access for workers with family responsibilities to flexible weekly work hours, location, and method (e.g., use of technology, job sharing, etc.) of work. These flexible work arrangements should be gender-blind, meaning female and male employees can take equal advantage of them.

As governments, employers, and employees all reap the benefits of increased worker flexibility, the costs of financing flexibility should be shared. Governments can lead the way by introducing best practice flexibility programs to their large workforces. They can also subsidize the costs of greater flexibility by providing quality, affordable childcare (0-5 years) and by synchronizing school hours with work hours throughout the day (e.g., by providing breakfast, afterschool, and occasional evening care) and the year (e.g., by providing all-Summer educational programs).

Governments could offset any increased costs to employers and workers through the tax and/or benefit system (e.g., by tax breaks, or conditional cash transfers). Employers could undertake cost-benefit analyses of introducing more flexible policies to determine the right mix of flexibility and finance any costs from profits or insurance schemes. Workers could contribute to the increased costs of flexibility by saving early in their careers and/or trading wage increases for greater workplace flexibility. As low-income families with dependent children currently incur a disproportionate share of the costs of the current system and have limited ability to pay for flexibility, governments and employers should prioritize any subsidies to them.

Finally, companies that introduce transformative policies, products and/or services enabling mothers to fully engage in the labor market should be celebrated. The world’s largest food and beverage company, Nestlé, offers 14 weeks of paid parental leave (up from six weeks) for 339,000 employees spread across 197 countries, with an option for parents to take an additional 12 weeks of unpaid leave. Multinationals Vodafone, Johnson & Johnson and Blackstone have also introduced new family-friendly policies, and national corporate leaders like Telstra in Australia have totally transformed the workplace by offering all workers access to an “All Roles Flex” policy.

Companies that offer new products or services that dramatically reduce household care burdens should also be celebrated including online retailers and delivery companies that dramatically reduce time spent shopping (e.g., amazon.com), cleaning/caring (e.g., care.com), and communicating with family members (e.g., apple.com). Governments could introduce new initiatives to ensure that these new products and services are available to low-income families.

The countries that have introduced more flexible workplace policies since 1990 (e.g., Norway, Sweden, and Finland) all now enjoy higher female workforce participation compared to those where masculine work norms still dominate (e.g., USA, Germany, Japan, Italy, and Spain). A study by Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn found that the lack of “family-friendly” policies including parental leave and part-time work entitlements explains 30% of the relative decrease in women’s labor force participation in the USA in recent years.

They caution however, that these policies also appear to encourage part-time work and employment in lower level positions and that American women are more likely to have full time jobs and to work as managers or professionals. It is critically important that more flexible work policies are designed to strengthen mothers’ long-term engagement with the labor market rather than further undermine it. Trade-offs need to be very carefully navigated.

A GLOBAL CAMPAIGN FOR THE CREATION OF NEW WORK NORMS

The United Nations (UN), its agencies, and development partners should campaign for the creation of new work norms offering workers unprecedented flexibility in when, where, and how they work, with a special focus on women with dependent children in the countries with high rates of poverty among families with dependent children and low female labor force participation.

Jody Heymann has exposed the shocking reality for too many families in low-income countries struggling to manage work and family responsibilities and the costs that are invariably born by their children, who already face multiple threats to their health and development. She argues that social policies in low- and middle-income countries have not kept pace with globalization and its impact on rising labor force participation and urbanization and, as a result, many of the world’s poorest families are raising children with limited adult supervision. Establishing new work norms in these countries will also contribute to global child survival and development goals.

Accordingly, the UN should prioritize eliminating the motherhood pay penalty as part of Sustainable Development Goal 8.5 (achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value), and 5.4 (recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate).

The UN should also champion the establishment of new work norms as part of the global child survival and related development goals as these policies will improve the capacity of families to prioritize the care of children and are ultimately an investment in future generations.

A Final Note. Our lives today are still defined by a set of profound separations that are based on the division of labor that first evolved in the family – man and woman, father and mother, work and home, public and private. Family life, work life, and even the physical structure of our villages, towns, and cities have embraced these divisions. It is likely that these divisions never served the interests of women or children, but at this point in history we have never been in a better position to do something to change that. We have never had a better opportunity to create families and workplaces that meet the distinct needs and fulfill the aspirations of all segments of the population – men, women, and children.

Updated January 2024